Jeff Hawkins

The man who almost single-handedly revived

the handheld computer industry

Part 2

GriD part 2

Back at GRiD, Hawkins was named Vice President of Research. He was described in one report from the period as "the architect of GRiD's pen-based computing program," and his GRiDPAD debuted in 1989.

"When he came back to GRiD," says Walker, "management wasn't sure where to place him in the organization, since he was more and more becoming a 'creative product architect,' and that didn't exactly fit into the structure of the traditional GRiD organization. So they gave him a VP title, put him in Engineering, and told him that he could do whatever he wanted. He didn't have anybody reporting to him, his role was just to create new ideas. As I remember it, this was when he created the GRiDPAD."

The First Handheld

The GRiDPAD measured 9 x 12 x 1.4 inches and ran on a 10MHz 80C86 processor. Naturally, at that speed, it ran DOS, Windows only being in its infancy at the time. Also, GRiD had its own software solutions written in GRiDTask. The GRiDPAD had a CGA (640x400) display, and cost US$2,370 without software. Data storage was via 256 or 512KB battery-backed RAM cards. Text entry was via pen, using his character recognizer engine, or via a regular keyboard that was attached with a cable. The computer's main target market was similar to many handheld pen slates today: field data collection in warehousing and transportation applications, as well as police, census takers, nurses; essentially anyone who usually used a form to collect data.

Ken Dulaney worked closely with Hawkins. "We worked on leading edge products for GRiD. The two of us always enjoyed lively discussions about the future and new product designs. Grid was a very creative place."

Geoff Walker concurs: "One of the characteristics of GRiD during all of the 1980s was that you could ask any person in the company--even an assembler on the production line--and they would be able to articulate the mission of the company. There was always a feeling of changing the world and a rock solid belief in the importance of what we were doing."

The GRiDPAD had many of the pieces in place that we expect in a modern handheld computer: a simple OS, a relatively efficient processor, removable storage, and a pen interface. But it didn't have small size, long battery life, light weight, and simplicity (DOS is simple, but not really easy). What it had in plenty was vision: the vision of empowering people with a computer that they could take with them, and empowering management with quicker access to data so that they could make better decisions and enable better customer service. Personal computers had done so much in just a few years to improve business, imagine how much more effective they could be if they could go with workers to where the data was.

At least that was GRiD's vision for the product. But deep down, Hawkins saw more potential. His vision was for smaller computers that would change people's ideas about computers altogether: computers that would change lives.

"After a while, around mid-1990, it became clear to Jeff that the best chance pen computing had for real success was in a handheld computer, and that the biggest market for pen-based handhelds would be consumers," said Walker. "So Jeff started creating paper designs for pen-based consumer handhelds, and investigating related technologies that would be needed to create such a product. Jeff developed a formal spec of a product he called 'Zoomer'--short for 'consumer'--and tried to sell GRiD's top management on it. They saw it as just too big of a risk. GRiD was focused on vertical applications of laptops and the GRiDPAD, and to start an entirely new product area aimed at consumers was seen as too divergent from the company's mission and focus."

GRiD had been purchased two years earlier by Tandy Corporation, so Jeff decided to see if Tandy would be interested in pursuing development of the Zoomer. "Around Christmas 1990, Jeff and I, and two other GRiD people met with Howard Elias of Tandy at the Fairmont Hotel in San Jose to try to convince him that they should build the Zoomer for GRiD," says Walker. "Howard's reaction was 'interested but cautious.'"

But they went for it, though it would not involve GRiD at all. With a license from GRiD for the software he needed, Hawkins left GRiD and founded Palm Computing on January 2, 1992.

He had Tandy, he had GEOWorks, and he had one of its board members, Bruce Dunlevie, backing him. It was Dunlevie's firm, Merril, Pickard, Anderson, & Eyre who would be Palm's main early investor. But he needed some help. Dunlevie had been looking for a person to work with Jeff in the new venture, and the name Donna Dubinsky came up. Dubinsky was looking for a company to make successful. It was a perfect match, one that is now legendary. Dubinsky's sales, management, and negotiating skills were a perfect fit with Jeff's enthusiasm, vision, and engineering talent. She joined the company in June 1992, and they were off.

"I was looking for an entrepreneur to partner with in order to build a big business," said Dubinsky. "I felt immediately that Jeff was a partner who could innovate great products, and that the space he was interested in, handheld computing, could be explosive. In a sense, it was an extension of my work at Apple, just taking personal computing to the next step." In a story that appeared in Fast Company, Dubinsky said, "One of my great purposes in life has been to create an environment where Jeff Hawkins can thrive."

Second tries

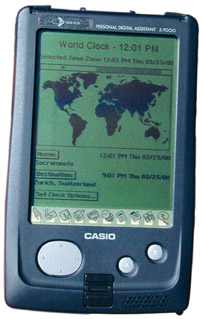

In the beginning, Palm Computing was only a software company. "We started Palm Computing with the thought that this would be like the PC world. And the conventional wisdom was that you wanted to be in software. That's where all the big money was being made: Microsoft, Lotus, Ashton Tate. So that's where it was happening and that's where I was being pushed from an investor's point of view. I wanted to create a handheld computer, a very successful computer product. So we structured it so that Palm would be doing the application software, we partnered with people to do the OS--I selected GeoWorks--we partnered with Tandy to bring it to market, and they brought in Casio to manufacture it, and then we added AOL and Intuit.

"While it sounded like a recipe for success, it was actually a recipe for disaster. What I learned through this process is that these computers are not little PCs. They cannot be designed by committee, because the Zoomer was designed by committee. You have to go against conventional wisdom in many aspects. We didn't know this when we built the Zoomer, we had a lot of problems in its design and we learned a tremendous amount doing it."

The Zoomer was a failure. It had many interesting data features, but it was slow, had bad text recognition, and, evaluated under the same public microscope as Apple's Newton, it went down as one of the first major handheld flops. Between October 1993 and January 1994, it had sold only 10,000 units.

"The Newton came out a few months before the Zoomer," said Hawkins, "but the Zoomer would have failed either way. It had a lot of faults. The Newton had lots of faults, too, and it would have failed no matter what. People tend to focus on the handwriting recognition problem--which was really kind of a red herring. Although it didn't work very well, and it was a problem, that was just one of many problems. In fact, we knew that handwriting recognition didn't work very well, so we really de-emphasized it. I almost didn't want to put it in there. But I was kind of forced to by the partners. I had a handwriting recognition engine that I created when I was at GRiD. But we de-emphasized it. We tried to focus on digital ink: to capture ink, shrink it down, do clever things with it. I hadn't thought of Graffiti at that time.

"And the Newton came out and trumpeted handwriting recognition, and of course it didn't work very well. People used to come up to me and ask, 'So, let me try your handwriting recognition.' I'd say, 'That's not what this is about.' I used to say, 'Anyone who thought they were in the pen computing business is going to go out of business.' I'm sorry to say that because of your magazine, but that's true, that's what I said. It wasn't about pen computing, it was about mobile computing, it was about information access. I believe that the pen is the best way of doing that, but if you focus on the pen, you're missing the point. We missed it too. We thought it was some other things. It turned out to be about things like personal organization, about being better than paper."

So they went back to the drawing board. Palm itself created software for several other handheld makers, including the Newton. The first version of Graffiti ran on the Zoomer and the Newton, acting as an alternative to "whole word" handwriting recognition. They also worked on the one-touch synchronization that would eventually become HotSync, and they refined their personal information management (PIM) software. At the same time, they tried to spec out the Zoomer 2, but no one wanted to build it.

The committee mindset was that any handheld had to have a large number of connections, so that it could connect to the company network, so that it could have a number of peripherals, including a keyboard, infrared, and removable storage. Jeff was constantly trying to convince people that it had to be smaller, it had to be simpler. After all, he had already done all that in the GRiDPAD and the Zoomer.

"As he traveled around, he became discouraged by the ineptitude of the companies out there to build compelling product," said Ken Dulaney. "Jeff is one of those rare people who knows not only what to put in, but more importantly what to leave out."

As reported in the San Jose Mercury News, Hawkins and Dubinsky went to talk with Bruce Dunlevie. They were looking for advice. What would they do if no one built a device that would succeed well enough in the marketplace? How would they sell software?

"Bruce said: 'Stop complaining about it. Do you know how to do it right?'" Hawkins remembers. "I said, 'Yeah, I do.' He told us to go back to the drawing board and do it ourselves."

The Charm

So Jeff considered his shirt pocket. He measured it. He grabbed a piece of wood and began to whittle it down to the right size. He put it in his shirt pocket. He walked around with it. For a pen, he whittled down a chopstick. He pretended to write on it. He mocked up what the screen might look like on a PC, printed it out, and taped it to the block, and continued to pretend to interact with it. Like the Hawkins/Dubinsky partnership, this story is already legendary.

"So we threw away the old business model as well as the old product designs," said Hawkins. "Let's take what we learned about these products, let's apply them to the new business model, which is building everything. We have to do the hardware, the software, the operating system, synchronization; make it all happen, and let's try to bring that product to market." Furthermore, the Pilot would not be a whole new product category unto itself; it would leverage off of the installed base of PCs, acting as a peripheral, easily sharing data with the PC via HotSync technology.

Key to this strategy was Graffiti. Like other programmers trying to create a handwriting recognition solution, Hawkins had been focusing on making computers read the way people write. Then he got the idea turn it around and get people learn how to write in a way that computers can read. "The beauty of Graffiti is that is doesn't work like handwriting recognition. It actually works like a keyboard. It is a keyboard analogy. It's instantaneous: you've got backspace, you've got punctuation, you've got space; you have an editing paradigm, which is exactly the same as a keyboard paradigm. It is a keyboard substitute. Handwriting just isn't a great way of editing things. There are all these gestures that are much harder to use. It takes you weeks or months to learn how to type, so why not spend 15 minutes learning how to do it with a pen?"

After another wrestling match with naysayers--who wanted to add more features--and the board of directors--who didn't think a small software company should presume that they could make the hardware and the OS--Hawkins had the go-ahead to make the Pilot.

In order to finance the considerably large undertaking, after a long search, Dubinsky attracted US Robotics, who ultimately bought Palm with a stock exchange.

Jeff worked with GeoWorks on the OS, and with US Robotics' manufacturing ability, they were able to bring the Pilot to market in the Spring of 1996 for the target price of under US$300. Today, Palm computers are the most successful handheld computers, holding a 70 percent market share, despite the many threats from competitors. Total calculated sales of Palm computers are well over five million.

Go to part 3 of 3

|